Borderdeaths

Borderdeaths is an incidents-based dataset. Each row corresponds to a dead body and an autopsy. Here are the chief causes of death:

The Deaths at the Borders Database (BorderDeaths) is an evidence-based database covering migrant deaths in the region of the EU external maritime borders. It accounts for migrant mortality in the Mediterranean from 1990 to 2013, starting when border deaths at the southern EU border emerged. The database collected evidence from death management systems of Spain, Gibraltar, Italy, Greece and Malta. As the first database that used official documentation, BorderDeaths brought together individualized information about each person who died attempting to reach the Southern shores of the EU without authorization and whose body has been found in or brought to one of the Southern EU member states. The database recorded 3188 people found dead in the accounted time period. BorderDeaths has been a five-year research project of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, funded by NWO, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (BorderDeaths 2017a; Last, Spijkerboer and Ulusoy 2016: 5f).

BorderDeaths aims to serve as a complementary resource to existing incidence based databases that are based on media reports or interviews. It was less interested in finding the exact number of border deaths, but rather collected the data to share it enabling other people to work with it. Therefore, the information has been collected in a way that made it accessible, while at the same time containing as much raw data as possible. Although not a direct aim of the project, BorderDeaths contributed to give a more complete and more nuanced account of the situation at the Southern EU borders (Interview Tamara Last).

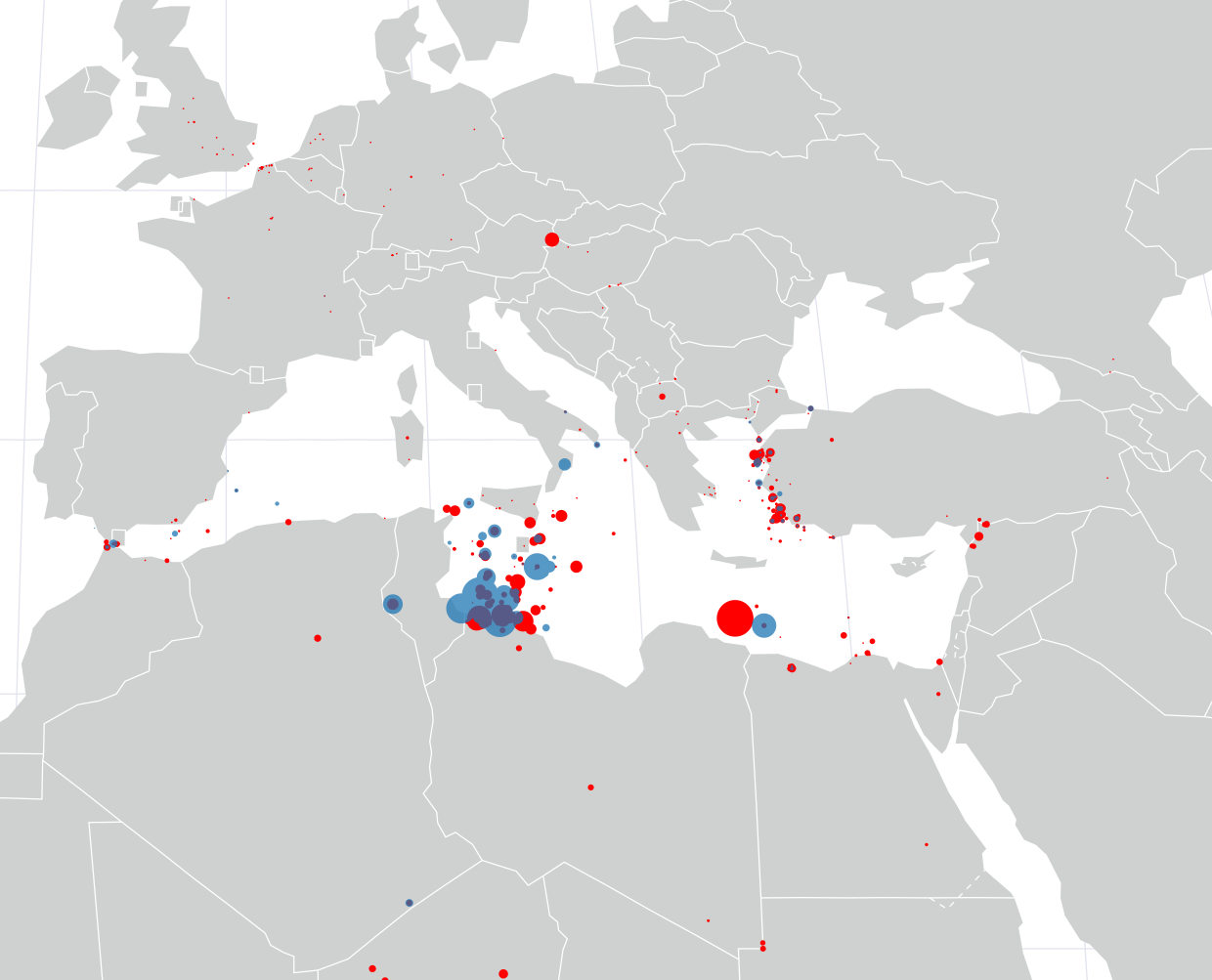

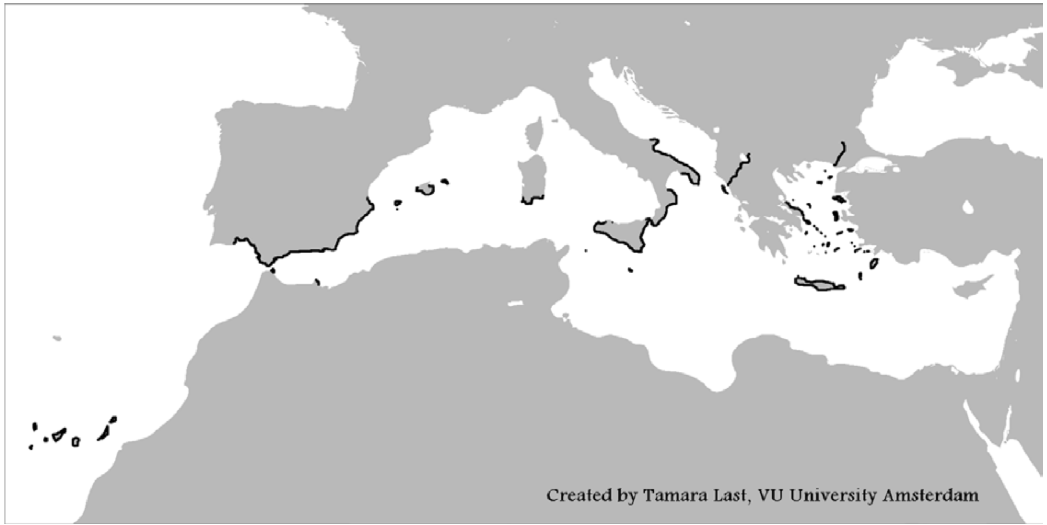

BorderDeaths collected data in the Southern EU member states, where irregular migrants have arrived or where bodies might be brought to. This precisely includes Spain (along the southern coast from Portugal to Valencia, at the coasts of the Baleares and the Canary Islands and in the Ceuta and Melilla), Gibraltar, Italy (Sicily coast and inland, southern coasts of Calabria and Sardinia, southern and eastern coast of Puglia, the coast of Foggia, the international port of Ancona, the major international port of Naples), Greece (the Cyclades, and eastern coasts of Evoia, the Dodecanese, Crete, the North Aegean islands, and the Greek side of the land borders with Albania and Turkey (Evros)) and Malta (BorderDeaths 2017b).

The project had been constructed with a European, or rather EU, bias, that has not been enlarged to other Mediterranean countries for mainly two reasons. First, BorderDeaths applied for research funding for a project with this scope and could not include other regions for financial reasons. Second, it started the research shortly after the Arab Spring and did not include non-EU countries for safety reasons. Following the methodology, the data collection has to be systemic and due to the political circumstances, large areas, for example in Libya, would have needed to be cut out. Yet, if done again, Turkey, Morocco, Mauritania and Senegal could be included (Interview Tamara Last).

The data base accounts for border deaths between 1990 and 2013 without the objective by the researchers to continue until the present date. Nevertheless, it would be easy to continue collecting the data. The death registries are all digitalized and centralized today. Since the method is already established, it would only be necessary to write a search program that searches for the criteria applied in the research to collect the data (Interview Tamara Last). Every person falling into the definition of border death was counted. Different degrees of certainty of a person being a border death were established. For this project, border refers to the physical borders of the EU, which included the high seas between southern EU states and North and West Africa (Last et al 2017: 710). It includes “[p]eople who have died attempting to migrate irregularly to Europe by crossing the southern external borders of the EU without authorization, whose bodies were found on or brought to the territories of Spain, Gibraltar, Italy, Malta or Greece” (BorderDeaths 2017b). This definition excludes people who died on the European continent, for example in detention, due to the limitations of the data collection method.

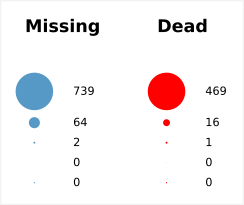

Border deaths were classed into three different categories: confirmed, likely and possible border death, depending on different levels of certainty that the person was a border death (BorderDeaths 2017b). The level of certainty was also established according to the amount of information available – the more information existed on a person, the more definite one could say, if he or she was a border death. The final count and the visualization include all the categories without distinctions.

Generally, a state does not establish whether a person is a border death, except for rare cases where it is marked in the death certificate. Therefore, criteria have to be set up to decide when a person counts as a border death (Interview Tamara Last). Counting border deaths based on death certificates has the advantages that they are easy to access, reliable in terms of avoiding double-counts and provide a useful summary of the identity and the death of the deceased (BorderDeaths 2017b).

The data BorderDeaths uses was collected in the death management systems of the geographical regions defined above. Since BorderDeaths was an academic project, the deaths were counted by twelve researchers and Tamara Last from 563 civil registries and additional offices in the period of April 2014 until February 2015 (BorderDeaths 2017b). A common methodology to search registries and extract data of border deaths was followed to collect data in a uniform way across the countries. The common methodology consisted of: a set of tools for collecting and recording data, a working definition of border death, a step-by-step manual on collecting the data in the archives and using the instruments (BorderDeaths 2017b, Last et al 2017: 699). The step-by-step manual clarified the steps when searching the books of the death registry, clarifying that researchers had to check every death certificate of the given time period. It also provided guidance on how to identify a border death, what details to look out for that hint at a border death. Identifying a border death was a process of exclusion. Persons with European nationalities, or with the place of birth or last residence in Europe were directly excluded. Death certificates of persons to whom these criteria did not apply were looked at more thoroughly (especially place of death, age and description of the deceased) and when nothing in the death certificate excluded the person from being a possible border death, it was recorded (Interview Tamara Last). Due to the logistics of data collections and some problems in the field, slight deviations from the common methodology were necessary in two cases.

After the data collection, all collected cases were reviewed and the degree of certainty of a case being a border death was established (BorderDeaths 2017b). The database contains of 43 categories. In many cases, not all of the categories could be filled in with the information of the death certificates because the data was not available or did not exist (Interview Tamara Last).

Borderdeaths - the academic dataset

| Interval | Total Death Count | Deaths per Day |

|---|---|---|

| 01.01.1990 - 31.12.1999 | 649 | 0.18 |

| 01.01.2000 - 31.12.2009 | 1708 | 0.47 |

| 01.01.2010 - 16.06.2014 | 831 | 0.65 |